Haemovigilance: Q&A with Paula Bolton-Maggs

Paula Bolton-Maggs is an Honorary Senior Lecturer, School of Medical Sciences, University of Manchester and retired former Medical Director of SHOT.

What is haemovigilance?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines it as: “… a set of surveillance procedures covering the entire blood transfusion chain, from the donation and processing of blood and its components, through to their provision and transfusion to patients, and including their follow-up. …The resulting modifications to transfusion policies, standards and guidelines, as well as improvements to processes in blood services and transfusion practices in hospitals, lead to improved patient safety.”1

How is haemovigilance organised in the UK?

The UK national haemovigilance scheme (known as Serious Hazards Of Transfusion (SHOT)), has gathered data since 1996 about unfavourable/adverse events and reactions related to transfusion. Reporting to SHOT is a professional requirement in the UK. The annual SHOT reports identify areas where laboratory and clinical practice need to be improved, highlighting learning points and making recommendations for change to improve patient safety and transfusion practice.2 For example, while blood components are very safe (transmission of infection in particular is very rare), our practice is often imperfect.

What are the most common hazards?

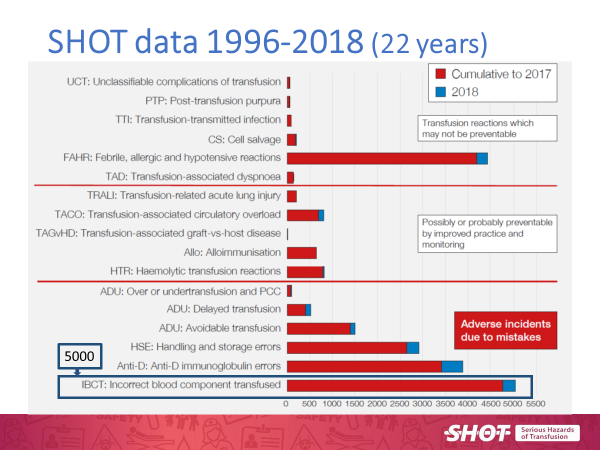

Since the beginning of SHOT 23 years ago most reported incidents are associated with human error (87% in 2018).

Over 22 years of reporting (1996-2018) more than 5000 patients have received a wrong transfusion, either a wrong component or one where the patient’s specific requirements (such as irradiation of cellular components) have not been met. However, to put this in perspective approximately 2.5 million units of blood are transfused in the United Kingdom each year.3

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the adverse incidents from 1996-2018.

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the adverse incidents from 1996-2018.

Does using an Electronic Identification System help to reduce these errors?

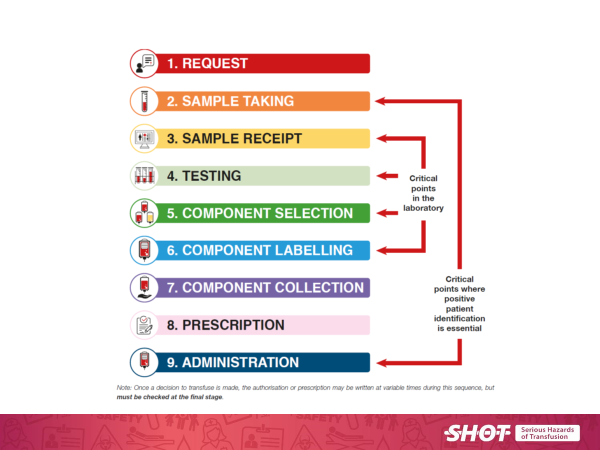

Electronic Identification System (EIS) procedures are safer than manual ones but must be set up and operated correctly. Staff must not become over-reliant on EIS, it is still essential to positively identify the patient by asking them to state their full name and date of birth. The hospital transfusion process is complex and involves many different people who each need to play their own part correctly. The basic steps are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Outlines the basic steps in the hospital transfusion process

Figure 2 Outlines the basic steps in the hospital transfusion process

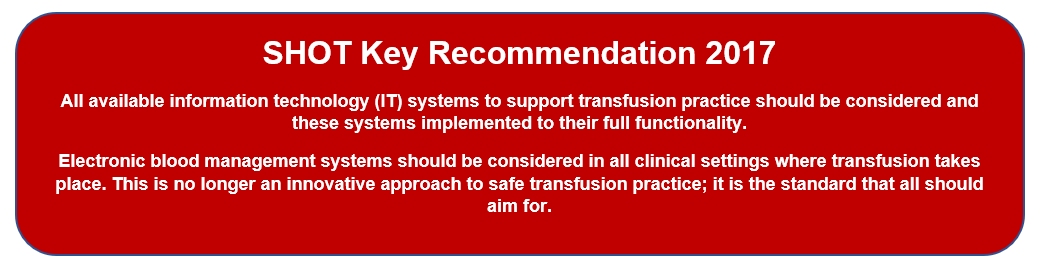

Information technology (IT) solutions can reduce error by removing humans from some of the processes. It is now recommended practice that all hospital transfusion laboratories use automated systems 24/7 for serological tests for transfusion.4

What is an ABO Group?

A person’s blood group can be categorised in several ways depending on the system used. The most common system is the ABO system, defined by A, B, AB and O blood group types. In order to group blood into these categories (ABO grouping), a test is performed to find out which antigens (in the case of ABO, an antigen is a combination of sugar and protein molecules) are present on the surface of the red blood cell. Blood is grouped according to the combination of antigens present, for example: no antigens present = Group O. Group A, B and AB all have antigens present.

Find out more information about the different blood groups.

What is an ABO/D Grouping error?

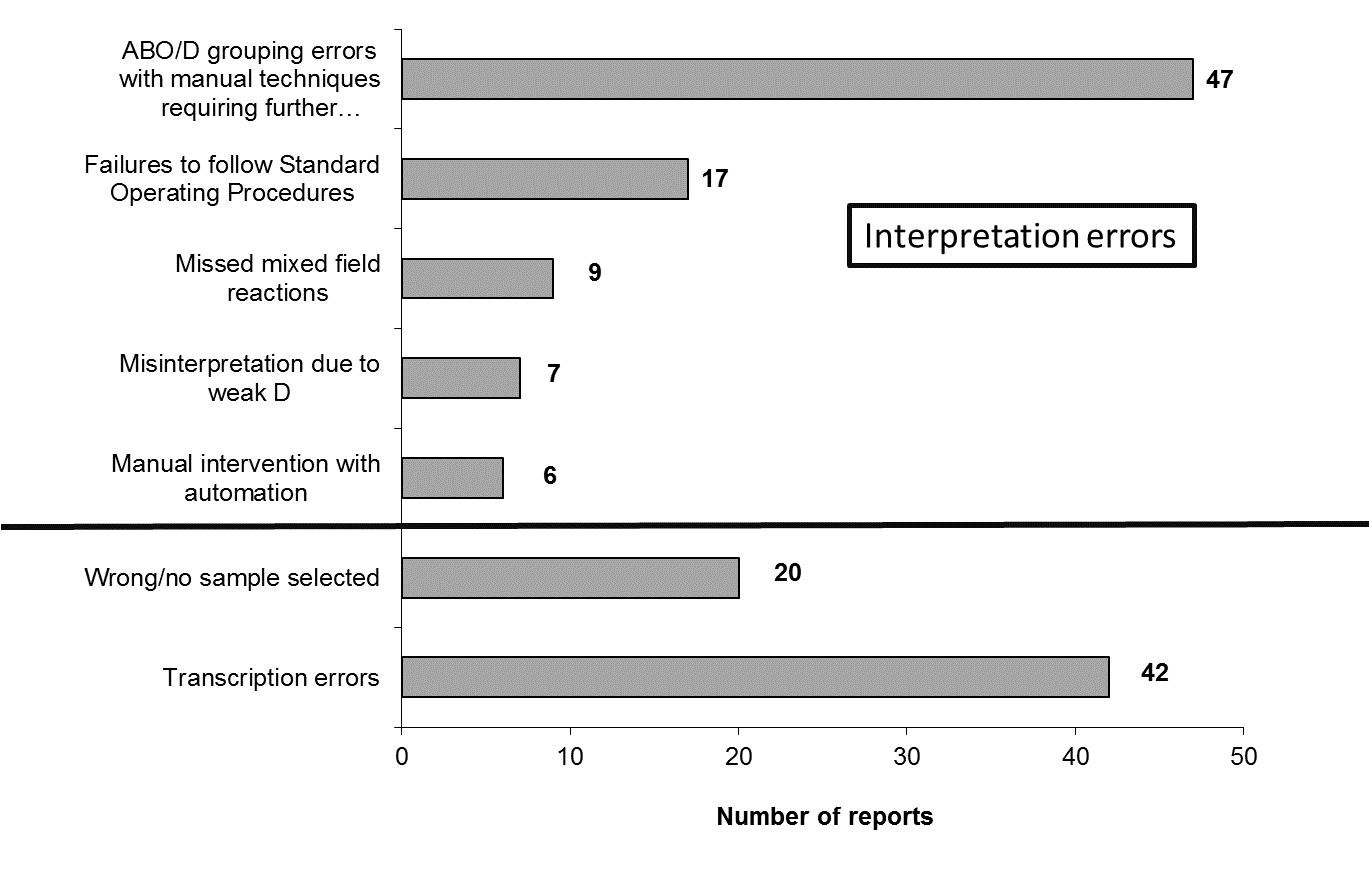

Human errors in manual pre-transfusion testing may result in ABO/D incompatible transfusions; this could be the result of a mislabelled blood sample tube, incorrectly completed forms, or other transcription errors.

In July 2019 SHOT published evidence to show that automation is associated with a reduction in ABO grouping errors compared to manual techniques. Between January 2004 and December 2016 158 ABO/D grouping errors were reported of which 148 (93%) had manual interventions. There were no errors with full automation. 5

ABO/D grouping errors involving manual intervention Figure 3 outlines ABO/D grouping errors involving manual processes

Figure 3 outlines ABO/D grouping errors involving manual processes

How has SHOT helped to reduce the number of transfusion errors?

Since 1999 SHOT has recommended increased use of IT across the full hospital transfusion process. There is increasing evidence that this improves safety and efficiency. Such systems should include the clinical patient identification points, from the blood sampling for transfusion through to administration of the component (vein-to-vein blood management systems). In the 2017 report SHOT made IT support for transfusion a key recommendation.

It is important to note, however, that IT is not fool proof. It must be set up and used properly.

One hospital set up a full vein-to-vein system with variations tailored to local preferences and not as designed by the manufacturer. An unexpected consequence occurred for more than 200 patients receiving transfusions, where the final bedside check was bypassed (fortunately with no clinical incidents). This was detected by audit and is fully described in the SHOT Report for 2015 (IT Chapter page 77).

How has EIS helped to reduce the number of wrong components transfused?

In 2017 SHOT performed a hospital survey and demonstrated that Electronic Identification Systems (EIS) reduce the number of wrong components transfused.6

What did we do?

All UK hospitals (222) reporting to SHOT were invited to complete an electronic survey about their use of EIS together with their numbers of incidents and near misses for wrong component transfusions in 2015 and 2016. The hospitals were asked about whether they used EIS for three key steps:

- blood sampling and labelling;

- blood collection and delivery to the site of transfusion;

- bedside checking at administration.

What answers did you receive?

93 responses in total were received (42%), and these 93 hospitals were responsible for 38% of blood component issues in 2015 and 2016 across the UK. Only 16 of the 93 hospitals (17%) use EIS across the full transfusion process, and 33 (35%) use manual procedures for all three steps. Most commonly, 36 hospitals (39%), EIS was in place for blood collection only.

Hospitals had implemented their EIS at different times. It should be noted that EIS are not used for all transfusions in all hospitals; this may be restricted to some departments. It is clear that uptake for IT is patchy and incomplete.

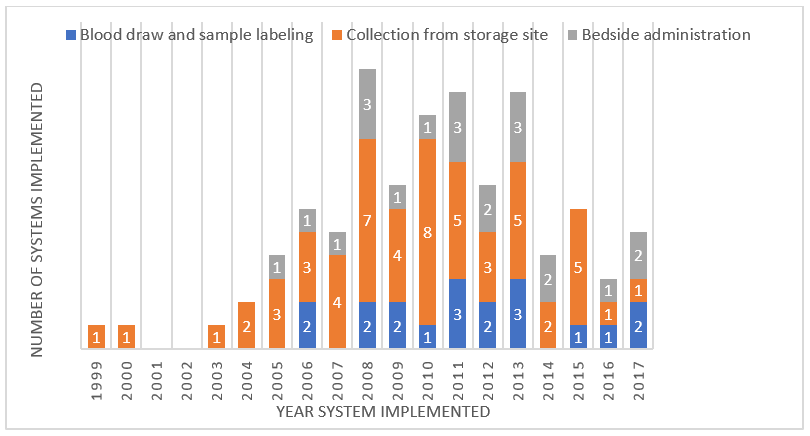

Figure 4 shows the uptake of IT systems from 1999-2017.

Figure 4 shows the uptake of IT systems from 1999-2017.

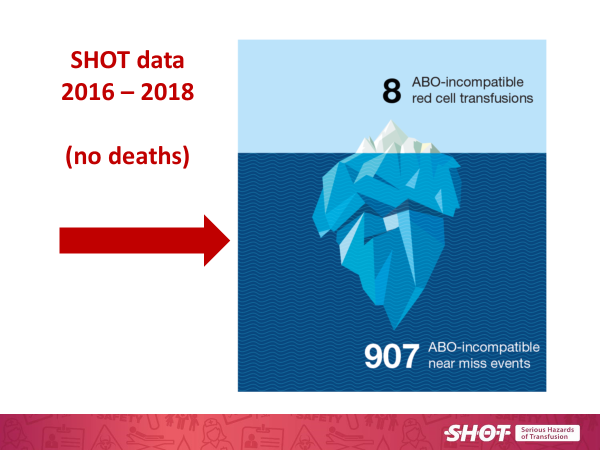

Wrong component transfusions may be fatal (e.g. some ABO-incompatible red cell transfusions). SHOT has noted that the number of near miss ABO-incompatible transfusions is considerably higher than the actual events, Figure 5.

What is a near miss event?

SHOT defines a near miss as an error or deviation from standard procedures or policies that is discovered before the start of the transfusion and that could have led to a wrong transfusion or a reaction in a recipient if transfusion had taken place.7

Do near misses also occur in transfusion?

Many near misses are caused by ‘wrong blood in tube’ samples detected by the laboratory staff, usually because there is a previous record with a different group. ABO-incompatible transfusions result from ‘wrong blood in tube’, laboratory errors, but most often from failure of patient identification at the final bedside check.

Figure 5 shows that the number of ABO-incompatible red cell transfusion near misses, is far greater than the actual events.

Figure 5 shows that the number of ABO-incompatible red cell transfusion near misses, is far greater than the actual events.

Did the hospital survey performed in 2017 ask about near misses as well?

Yes, it did. 85% (484/571) of reported near miss errors occurred with manual procedures; most of these were errors at sample taking and labelling and detected in the transfusion laboratory. There were 37 near miss incidents related to EIS, 17 at blood sampling and 20 at administration.

The rate of near miss was 1 in 3,474 for manual processes and 1 in 22,137 for EIS confirming improved safety.

The 17 near miss incidents at blood sampling with EIS are a warning that care needs to be taken when generating electronic labels that this is done at the bedside with the wristband on the patient.

What is the take home message?

EIS procedures are safer than manual ones but must be set up and used correctly. Staff must not become over-reliant on EIS, it is still essential to positively identify the patient by asking them to state their full name and date of birth.

The use of EIS by hospitals is patchy and it is rarely used to its full potential. Hospitals should be encouraged to benefit from the increase in patient safety that full vein-to-vein EIS can provide.

References:

Follow us on Twitter