Questions, questions and yet more questions

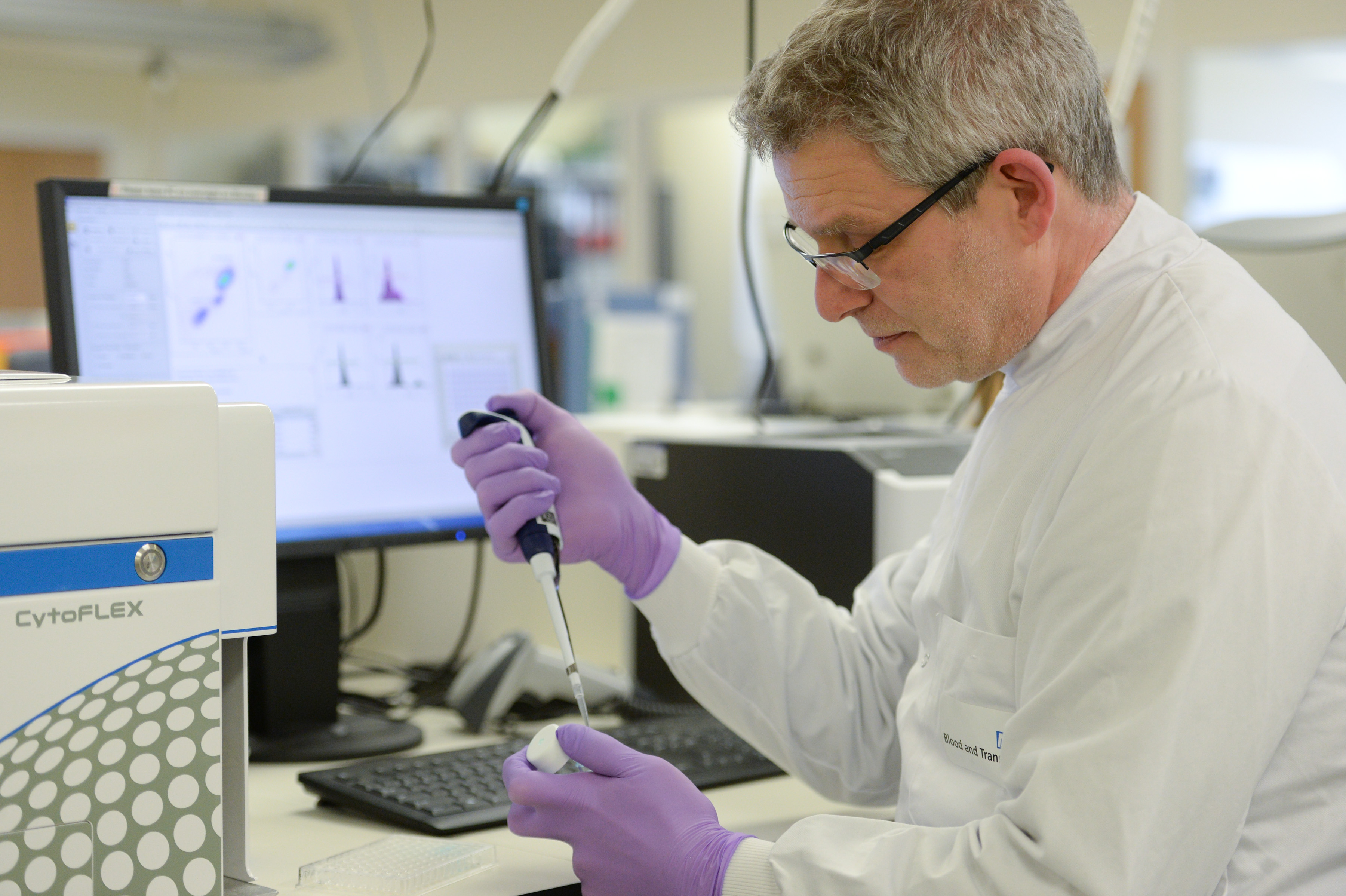

Mr Jonathan Dixey is the Laboratory Manager of the Protein Development and Production Unit (PDPU), which is part of the International Blood Group Reference Laboratory (IBGRL), based at Filton, Bristol.

Questions, questions and yet more questions. We’re raised on them and start demanding answers to our own as soon as we grasp the meaning of that potent little word ‘why?’

Are we hard-wired to be curious or just conditioned - nature or nurture? Probably both, but feel free to ask your favourite search engine (one of the most inevitable technological advances of all time, probably invented by a harassed parent).

Some people are lucky enough to earn their living asking questions, like those of us working within the field of Research and Development (R&D) at NHS Blood and Transplant. Many years ago, a young lecturer I knew described the scientific process as ‘asking questions’. Deceptively simple, but it’s still one of the best definitions I’ve heard.

Of course, asking the right questions and devising sound experiments to discover the answer are crucial – that’s where scientific training and experience come in. That particular lecturer kept on asking so many questions about the immune system that they finally banished him to his own office (with a big sign on the door saying ‘Professor’), but that still didn’t shut him up.

In the Protein Development and Production Unit (PDPU) at Filton, we specialise in making monoclonal antibodies and recombinant proteins. If that all sounds like a bit of a mouthful, just think of these reagents as tools that allow researchers and clinical scientists to answer medical questions.

In the Protein Development and Production Unit (PDPU) at Filton, we specialise in making monoclonal antibodies and recombinant proteins. If that all sounds like a bit of a mouthful, just think of these reagents as tools that allow researchers and clinical scientists to answer medical questions.

Just as the antibodies made by our immune system are able to pick out one rogue protein from the many thousands of ‘self’ proteins – a kind of biological identity parade – those that we make in our lab can also seek out and identify a specific target.

Because of this property, antibodies have been used in tests designed to answer all manner of questions. If you want to know if you’re pregnant, there’s an antibody for that (it reacts with hCG and is the basis of the pregnancy test), and should the answer be yes, then one of the blood tests we have developed might well come in handy later on.

Foetal red blood cells sometimes leak into the mother’s blood stream, and under certain circumstances they can ‘vaccinate’ the mother, causing problems for future pregnancies. In the PDPU we produce an antibody that can seek out foetal red cells hiding in the mother’s circulation – no easy feat, because they look really similar.

Accurately quantifying these intruders with our antibody means that clinicians can remove them, before the mother’s immune system has a chance to react. This increases the chances of later pregnancies progressing without a hitch and is just one example of how we have tried to address the question that drives all of our research – how can we have a positive impact on the health of our patients? Medical science is progressing on every front but there is still so much to learn. Each discovery generates a host of new questions, but fortunately, the scientists at NHS Blood and Transplant and beyond are a stubbornly curious bunch and refuse to throw in the towel.

Medical science is progressing on every front but there is still so much to learn. Each discovery generates a host of new questions, but fortunately, the scientists at NHS Blood and Transplant and beyond are a stubbornly curious bunch and refuse to throw in the towel.

As long as this is the case, my colleagues and I in the PDPU will be kept busy, devising novel strategies to assist them in their quest for answers (Image left: the Protein Development and Production Unit team).

New treatments for disease bring hope to many but also raise challenges for patient management. Our current research is focused on making the necessary tools to meet these obstacles head on.

Will we ever have all the answers? Not a chance. But as long as we know a little more now than we did yesterday, we’ll keep on asking questions.

Follow us on Twitter